Kobe Bryant’s Mamba Foundation. Jay-Z’s Shawn Carter Foundation. Alicia Key’s Gordon Parks Foundation. What do all of these have in common? They desire to share their wealth to create a better world with the chance at a better life for everyone.

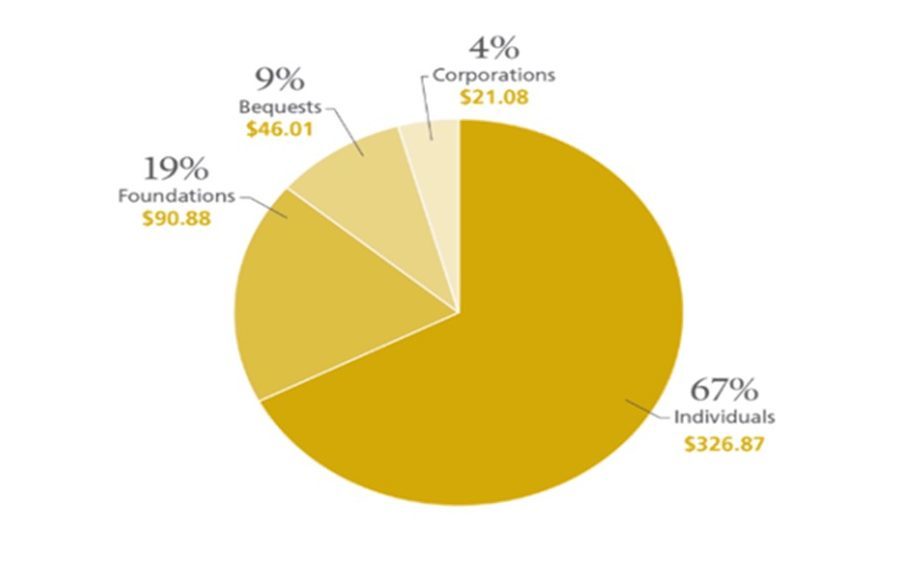

Philanthropic foundations first started appearing after the Civil War with George Peabody at the forefront, donating half of his $16 million dollars to charity. With his pioneering Peabody Education Fund, he is known as the “father of modern philanthropy”. Following his lead was a number of foundation creators in the early 1900s including Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller. Generosity is a long-standing American tradition, one that continues to grow. According to the Giving USA 2021 Annual Report (Figure 1), Americans gave $484.85 billion in 2021. This reflects a 4% increase from 2020. In 2021, the largest source of charitable giving came from individuals, who gave $326.87 billion, representing 67% of total giving. Corporate giving in 2021 increased to $21.08 billion—a 23.8% increase from 2020. Foundation giving in 2021 increased to $90.88 billion—a 3.4% increase from 2020.

In the US, charitable gifts of money account for about 2.1% of the GDP. In addition to monetary donations, an estimated 30% of US adults, 77.9 million Americans, volunteered in 2019, contributing an estimated 5.8 billion hours, valued at approximately $147 billion.

Economists are becoming increasingly aware of the need to better understand philanthropic activities. There are more than 1.54 million charitable organizations in the United States and they are viewed as firms that hire inputs to produce goods and services. By viewing philanthropy as a market, economists are trying to analyze the interplay between donors, charitable organizations, and the role of the government. “Who gives? Who are the recipients of these gifts? Would changes in the tax treatment of charitable contributions lead to more or less giving?” (List, 2011). Answers to these questions are important factors for fundraising efforts, assessing charity efficiency, and designing public policy.

Is philanthropy good for the economy?

The answer is a simple, yes. “Due to a multiplier effect, services and activities enabled by donations and provided by charities create downstream economic benefits (Pitt et al, 2021). A review by the National Council for Nonprofits shows that non-profit organizations bolster local, state, and national economies in multiple ways, including:

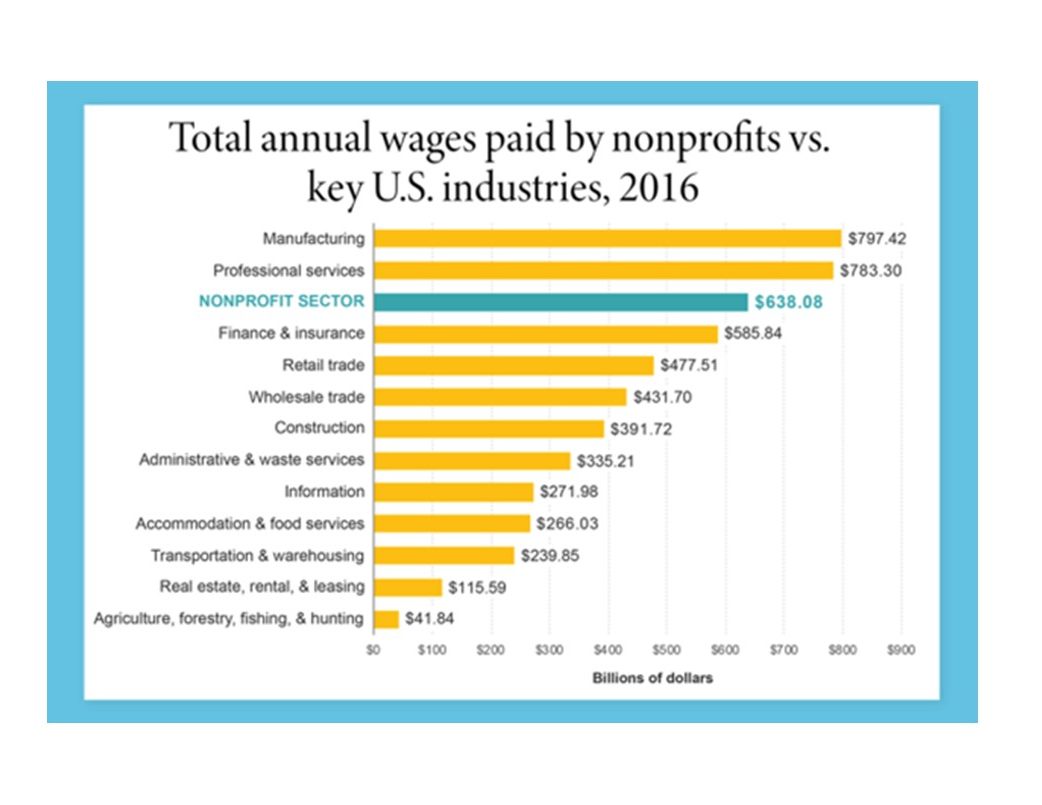

- Non-profits create jobs: Non-profits employ 12.3 million people with higher payrolls than most other US industries, including construction, transportation, and finance (Figure 2). About $638 billion out of $2 trillion are allocated to employee salaries, benefits, and payroll taxes each year. Also, these employees pay income taxes on their salaries, as well as sales taxes on their purchases and property taxes on what they own.

- Non-profits free people from responsibilities: Organizations that provide care to dependent children or elders allow family members, who would be forced to stay home, to work outside the home. Many non-profits provide job training and placement services for people who would otherwise be unemployed or underemployed.

- Non-profits consume goods and services that create more jobs: Non-profits spend almost $1 trillion annually for goods and services, ranging from large expenses, like medical equipment for hospitals, to everyday purchases of office supplies, rent, and utilities.

- Non-profits stimulate economic activity: Non-profits help to create jobs for the local community, which helps to generate more tax revenue for the local government. For example, by attending a dance performance for a charity, you not only support the dance crew but also the theater and theater staff. Food catered for the event would boost local catering companies.

- Non-profits build partnerships across different sectors: Business leaders recognize the great value that local profits contribute to the community’s overall welfare, so they will often partner with non-profit groups for mutual benefits.

Why do people give?

As mentioned before, economists study various factors affecting philanthropy. Economists assume that people are self-interested and since individuals have a choice in how they behave in a given situation, they must always make the choices that they think are the best at the time. This assumption, called the ‘axiom of rationality, provides the basis for economic behavior models of philanthropy. Studies suggest that people are not entirely altruistic when giving (Murillo & Roisman, 2005).

According to the theory of “Perfect Altruism”, donors are concerned primarily that charities receive some total amount of money, regardless of the sources. So if a charity needs $1000 and they have collected already $800, that individual donor would donate the remaining $200. If the charity already collected $1000, they would not contribute. This follows the “Public Goods Model” where people are more interested in what their gifts accomplish, rather than the actual dollar amount. For example, a person donates to a cancer hospital, so that one day they can benefit from the services provided there. One implication of this theory is that individual donations could get completely “crowded out” by government contributions. If the government taxes the donor $100 and hands it over to the charity, the donor would reduce their contributions by $100. However, studies have shown that “crowding out” is only a partial explanation. Most donors are found to get more satisfaction from giving a dollar directly to a charity than they do from seeing a dollar of their tax money given to that same charity. The “Perfect Altruism” theory also falls apart when the number of donors is very large. People would anticipate that the larger donors would give sizable contributions, so they would contribute less. But data does not support this and instead, people from all income levels were found to give. In addition, this theory does not explain the fact that many people volunteer their time to charities, which implies an opportunity cost to individuals as they could work elsewhere to gain wages (Murillo & Roisman, 2005).

The second theory of giving is that people get something directly from charity in exchange for their contributions. For example, big donors may get tickets to a game or their name put on a building. One study shows that when the names of donors are publicly announced and gift amounts are given in categories (ex: $100-$499, $500-$999), most contributions were the minimum amount for inclusion in each category. This preference for prestige implies that charities can increase contributions by reporting gift categories and publicly announcing donations. While this theory partially holds true, it does not explain why people continue to give even when the exchange is small (ex: pen) (Tayyab, 2021). After analyzing various theories of giving, economists have found that the “Warm-glow” theory is a core economic motivation for giving. According to this theory, people donate because they derive internal satisfaction from giving. They want gifts to come from themselves rather than others. This theory becomes consistent with the thought that “crowding out” does not influence people’s motivation for giving. People do not view voluntary contributions and involuntary giving through taxes as the same, therefore government taxation does not reduce private contributions by the same amount. This theory is consistent with the fact that many people volunteer their time to charities. The “Warm Glow” motivator for giving is a basic human interest to help others and do one’s share (Minardi & Evren, 2021).

Who Gives?

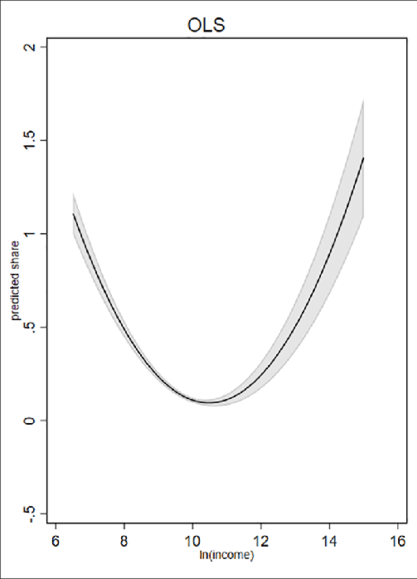

Many factors have been studied to determine the population of people who donate. Income was found to be the most important predictor of giving behavior. Giving as a function of income has a U-shaped pattern (Figure 3), where people in the lowest and highest income groups give larger proportions of their incomes to charity rather than middle-income groups.

Many factors have been studied to determine the population of people who donate. Income was found to be the most important predictor of giving behavior. Giving as a function of income has a U-shaped pattern (Figure 3), where people in the lowest and highest income groups give larger proportions of their incomes to charity rather than middle-income groups.

An explanation given for this trend is that low-income groups tend to give to more religious organizations and higher-income groups have more disposable income and the highest marginal tax rate, giving them the greatest incentive to donate because they face the lowest marginal cost of giving.

Also, charitable giving is found to increase with age and education and women tend to give more than men (Mcclelland & Brooks, 2004).

Who do people give to?

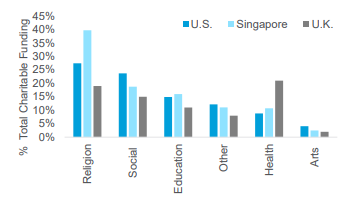

The most popular destination for donations is religious organizations as religions often emphasize the importance of humanity and service. These organizations provide support to other secular causes. Other areas that benefit from philanthropy include education, healthcare, and international aid. Figure 4 shows these trends. However, these sector titles are very broad, and more research needs to be done to understand the dynamics of supply and demand of philanthropic funding by breaking down these sectors into smaller causes. More specific data could help donors and charities select causes and donate with a greater impact. Money can be supplied to those organizations with greater demand. Donors tend to give to the causes that are closest to them — the causes with which they have the greatest empathy. This often leaves a gap in funding organizations that are less connected to donors. And more research needs to be done on the allocation of funds to specific departments within the charities in order to maximize the benefits of philanthropic donations (Pitt & Kardos, 2021).

Future Trends of Philanthropy

It is expected that a number of trends will impact philanthropy in the coming years (Pitt & Kardos, 2021), including:

- Demand for philanthropic capital will remain elevated as charities continue to play a key role in the COVID-19 pandemic recovery.

- The increasing role of technology presents a huge opportunity for charities to transition to a digital or hybrid service. There will be an increase in digital service goods along with digital volunteering opportunities and fundraising campaigns.

- Today relatively few charitable dollars support environmental causes. With the increasing awareness of climate change and biodiversity loss, public, private, and charity sectors can be brought together to combat this global problem.

- There has been a rising sense of corporate social responsibility which will affect how corporates behave in the world. There is a growing trend for skills sharing between charities and the corporate sector, particularly in facilitating technological development.

- It is expected that activism and philanthropy will move closer together in the coming years. Younger donors tend to connect donations with social action.

- Post-pandemic, funding structures have changed as grantmakers waived certain provisions to allow charities to focus on service delivery. There is an opportunity to review the success of these adaptations and the possibility of less restrictive funding for charities to continue.

Philanthropy has come a long way from the times of Peabody, Carnegie, and Rockefeller. As economists continue to study the dynamics of giving, technology, and social impact trends, we can hope to see a new era of philanthropy evolving, inspiring millions more to create a better world.

References

Giving USA 2021 Annual Report. (2021).

https://givingusa.org/

List, John A. 2011. “The Market for Charitable Giving.” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 25 (2): 157-80.

Mcclelland, R., & Brooks, A. C. (2004). What is the Real Relationship between Income and Charitable Giving? Public Finance Review, 32(5), 483–497.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1091142104266973

Minardi, S. & Evren, O. (2021). How to Explain Warm-Glow Giving. HEC.

https://www.hec.edu/en/knowledge/articles/how-explain-warm-glow-giving

Murillo, H. & Roisman, D. (2005). The Economics of Charitable Giving: What Gives? Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis.

https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/regional-economist/october-2005/the-economics-of-charitable-giving-what-gives

National Council for Non-Profits. (2022). Economic impact.

https://www.councilofnonprofits.org/economic-impact

National Philanthropic Trust. (2021). Charitable Giving Statistics.

https://www.nptrust.org/philanthropic-resources/charitable-giving-statistics

Pitt., A., Thompson, A., & Kardos, K. (2021). Philanthropy and the Global Economy. Citi GPS: Global Perspectives & Solutions.

https://www.privatebank.citibank.com/newcpb-media/media/documents/insights/Philanthropy-and-global-economy.pdf

Tayyab, A. (2021). Economic Dimensions of Philanthropy. Dawn.

https://www.dawn.com/news/1639558