On a visit to the mall, you may have seen a large selection of toy vending machines lining the wall at some point. If you looked a little closer, you would have probably seen an array of figurines with the odd ring or accessory added to the mix. These machines originate from Japanese toy gashapon/gachapon vending machines and are the origin of the gacha mechanic, a system where people exchange currency to receive random items. This mechanic has since been implemented online in a wide array of mobile and PC games like role-playing games (RPGs) and first-person shooters (FPSs), even leading to the formation of a new genre of games–Gacha games.

The basic mechanic of online gacha games is that it introduces randomness into monetization. The game sells some of its items, which can range from characters to weapons to skins, through a gacha mechanic where the player must “pull” or “roll” for a chance to get the items that they desire. The player’s end goal is usually to obtain the characters, weapons, skins, or items that will make their gaming experience more enjoyable, whether it be in the form of increased combat power, unique gameplay, or aesthetic cosmetics.

The Gacha game industry is extremely lucrative. One notable example is the open-world RPG Genshin Impact (GI) which made $2 billion in profits in its first year alone. Aside from Genshin Impact, the gaming industry reached a market size of $85 billion in 2021 in the US alone, with 60% of the top-charting games featuring some gacha element. This is partly because the games have successfully implemented behavioral economics theories into their marketing tactics. These theories include the availability heuristic, bounded rationality, loss aversion, sunk cost fallacy, anchoring effect, and psychological pricing theory.

Availability Heuristic

The availability heuristic is the idea that people often rely on easily recalled examples, information, or experiences rather than proper data when evaluating something (a situation, probability, etc.). For example, a person may think that plane crashes are more common than car accidents because they’ve seen more about plane crashes on the news, or a doctor may be more likely to diagnose a certain condition if they’ve recently treated that condition before. In the world of gacha games, it’s not uncommon to see social media posts of people’s impressive gacha results online. These posts may cause an individual to overestimate the probability of having similar luck in their pulls.

Bounded rationality

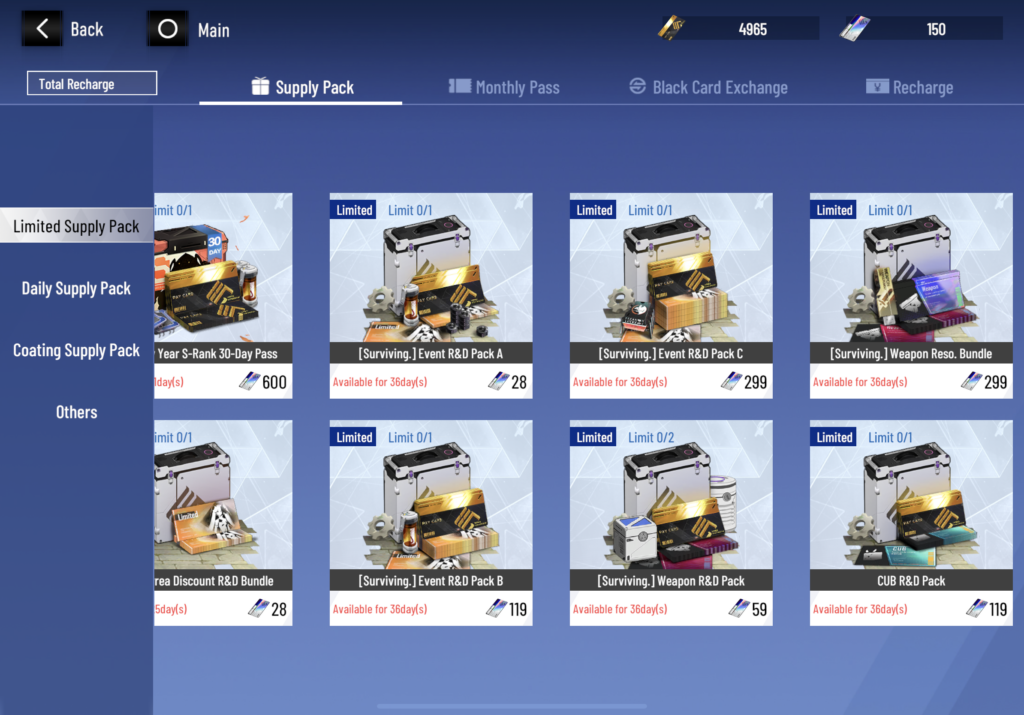

Bounded rationality is the idea that people are not always perfectly rational and that their decisions are often influenced by factors such as available information, time constraints, limited computational abilities, or impulses/”go with your gut” moments. For example, an individual may struggle to pick which brand of eggs to get if there are too many options, in which case they may pick whichever one catches their eye first. In gacha games, this effect can be observed in numerous aspects, such as the abundance of special packages available at one time and the complex conversion rates between currencies. This often makes it difficult to determine which package has the highest value.

Loss Aversion

Loss aversion is the idea that people dislike losing more than winning. For example, the thought of losing a $1000 bonus is much more painful than the thought of gaining a $1000 bonus. In gacha games, loss aversion can be observed in monthly passes and limited time banners. Many gacha games offer monthly passes where players can receive rewards daily upon logging in. These monthly passes are active even when the player does not come online, meaning that the rewards for a day will be entirely lost if the player doesn’t log on that day. In the case of time-limited banners, not being able to obtain a character before the banner ends can induce a feeling in players that they lost the character.

Sunk-Cost Fallacy

The sunk-cost fallacy is that a person may be reluctant to abandon a strategy/project if they’ve already invested too much in it, even if it would be more beneficial to abandon the said project. For example, a person might continue investing in a failing company solely because they’ve already invested too much into the company and cannot accept that they made the wrong decision. In gacha games, this can take many forms. For example, players may need to continue logging onto the game daily because they’ve already “made an investment” by buying a monthly pass.

Anchoring Effect

The anchoring effect refers to how people have a tendency to base their decisions on an “anchor,” which is often the first piece of information offered about the decision. For example, in one experiment, retail agents’ evaluations of a property were shown to be influenced by the asking price of the property owner. An example of the anchoring effect in gacha games can be found in Genshin Impact’s package pricing. GI presents two packages for the same price of $4.99, one of which is essentially ten times more valuable than the other. The less efficient package works as an “anchor” for GI’s currency, making the more efficient package seem that much better.

Psychological Pricing

Psychological pricing is the idea that the number 9 is more attractive to people. For example, the University of Chicago and MIT conducted an experiment in which a clothing item was sold for $34, $39, and $44 to three sample groups, respectively. In that experiment, items priced at $39 sold more often than items priced at $34 or $44. Psychological pricing can be observed in all kinds of items ranging from expensive electronics like TVs and phones to much cheaper things like food items. Gacha games are no exception–practically every gacha game’s purchase options end with a “$-.99” figure.

Many gacha games may appear to be free-to-play and can be enjoyed without spending at all. However, it is crucial to remember that gacha games can be addictive and often encourage the player to spend lots of money. While spending on a game is okay as long as you can afford it, it is important to take a moment to rethink spending decisions to see if they are worth it.

References

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gacha_game

https://news.uchicago.edu/explainer/what-is-behavioral-economics

https://www.behavioraleconomics.com/resources/mini-encyclopedia-of-be/availability-heuristic/

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/bounded-rationality/#GameTheo

https://www.pon.harvard.edu/daily/negotiation-skills-daily/the-drawbacks-of-goals/

Kahneman, Daniel. Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013.

Genshin Impact Shop Menu

Punhsing: Gray Raven Shop Menu